Les Crocker

In 1978 art history professor Les Crocker went down to visit the Odin J. Oyen building to meet with Leighton Oyen. Once there, he and his colleague discovered that many of the company’s original designs and drawings still existed in the old building. Now that collection is housed at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse.

Transcript

Location: 108 5th Ave. North

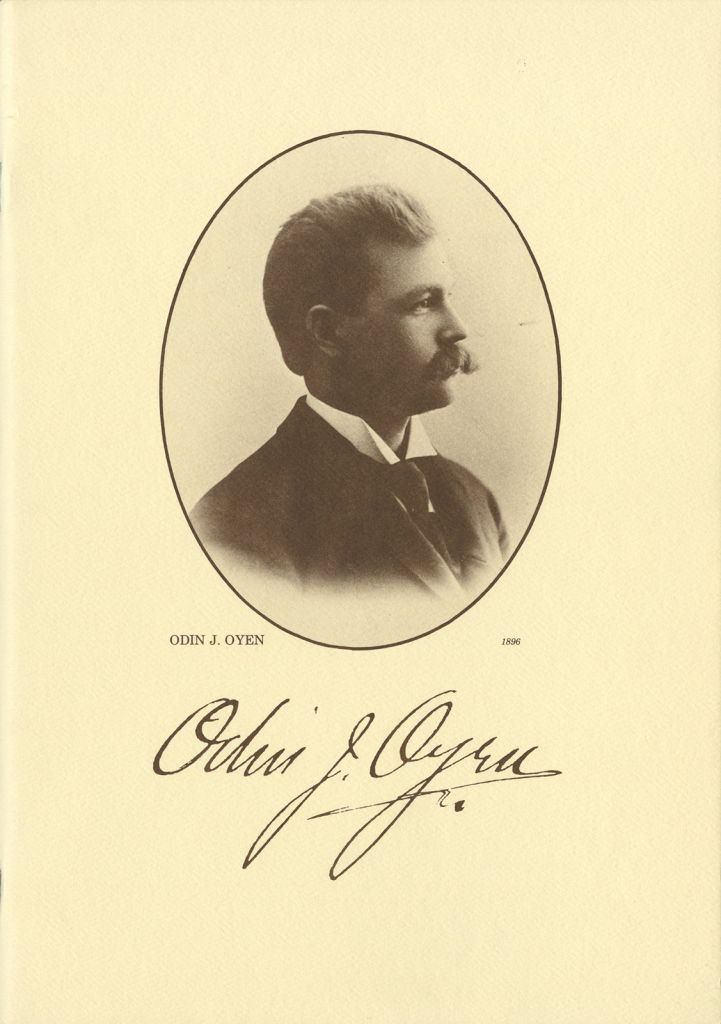

The Odin J. Oyen building here on Main Street is a very interesting, unusual building, and it played a role in the Oyen Collection that’s at the university. The Oyen Collection came about really as an accident. Joan Rausch, who had been a nurse for many years, came back to the university after her children were grown, and she got interested in local history, but she was interested in the building and in her research, she realized that Leighton Oyen, the son of Odin Oyen, was still alive. From there we learned that there were many designs and drawings from the firm still in existence, and early one Sunday morning in the fall of 1978, Joan and I came down to the Oyen building and met with Leighton.

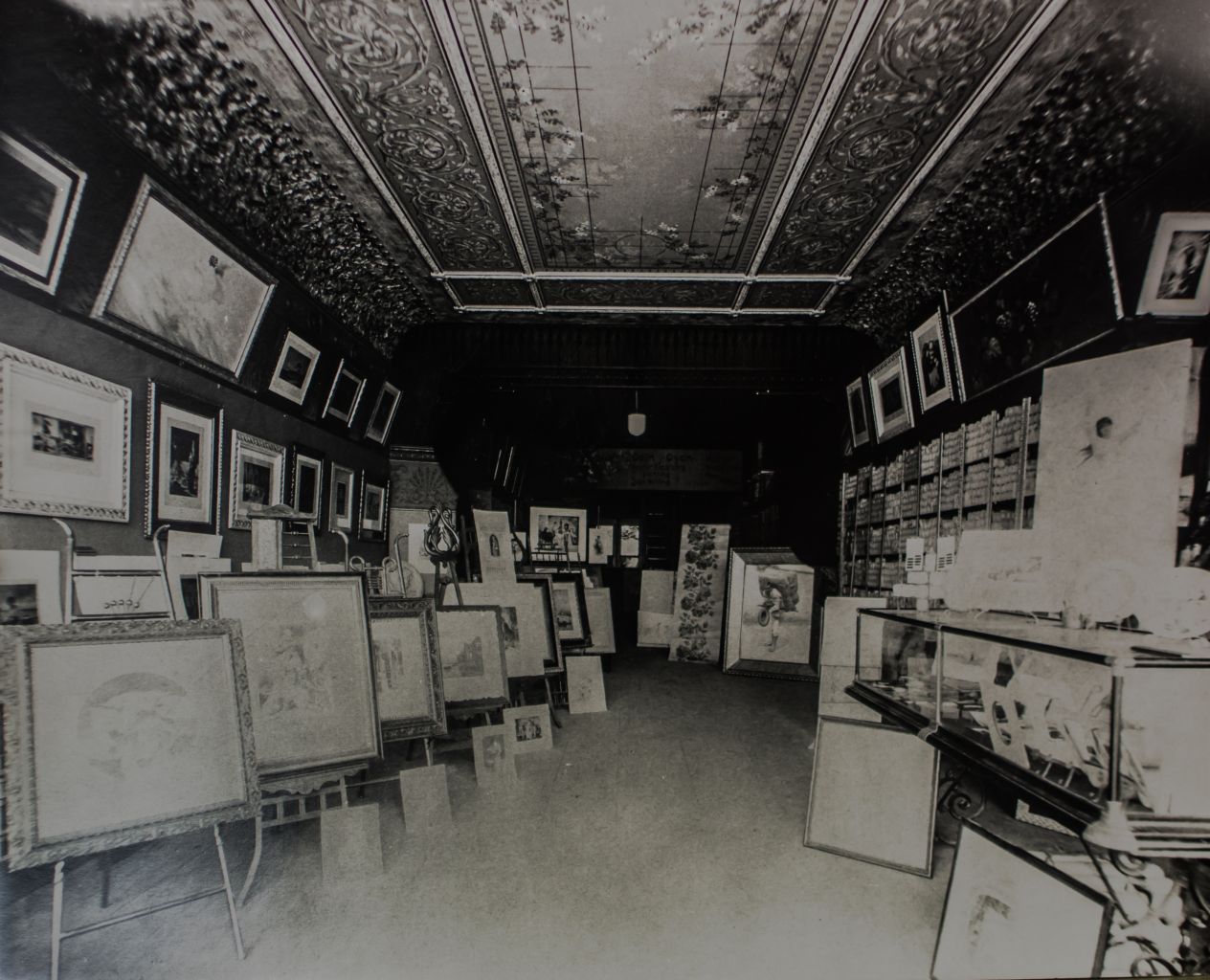

There was a big liquor store on the ground floor of the building, I don’t remember now what was on the second floor, but the third floor was the old studio of the Oyen decorating company. It was a completely open space from the front to the back of the building. I remember several large, wooden easels pushed back against the wall, and there was a large oil painting hanging on one wall. Every flat space on that floor was covered with stacks and stacks of paper. Designs, drawings, presentation pieces, all sorts of visual material mixed together. Some of it was covered with dust that looked to be thirty or forty years old. Other piles had been looked at more recently. But as Joan and I went through them and blew the dust off and looked at the images, it was obvious that these were very important remains of the Oyen Company.

Leighton agreed to donate the material to the university, and Joan and I really grabbed the material and ran. We hauled it downstairs and put it in our cars. The painting we took off the stretcher and rolled it up and I carried it over to the university on top of my little Ford Mustang.

It was really important, we felt, to get the material then, while Leighton was willing to sign the papers. He had made agreements and not kept them before so we really thought it was important to get the material.

When we were up there, in the third floor studio, it was obvious that there was an awful lot of raw material here, and it’s the raw material that disappears the easiest. The paintings, the frescos, they tend to survive, but the drawings that tell us what the artist intended, what he was thinking, what he was figuring, often get lost, so all of this material is sort of the backstory on the final works of art.

In the ‘70s, the Oyen Building had suffered a great deal because of a large liquor store that was in the ground floor and there was a large metal sign across the front of the building that obscured part of the ground floor and part of the second floor. So you couldn’t see the nice stonework, you couldn’t see some of the brickwork on the second floor. So a truly distinguished building had been made rather ugly by one of the metal signs that were quite numerous in the downtown during the 1950s and ‘60s. Fortunately, the building has been restored now to its original appearance and contributes much to the community.

I’m Les Crocker. I taught art history at the university for thirty-two years, became interested in the buildings of La Crosse, and have spent the last forty years of my life researching and writing about the architecture of La Crosse.